Mental Health – What we already know

What we already know

Poor mental health has a considerable impact on individuals, their families and friends, and the wider community. Overall rates of psychiatric disorder are roughly the same for both men and women, but there are significant gendered differences with regards to patterns of mental ill health. Women experience more depression and anxiety, but suicide rates remain consistently higher for men.

Poor mental health is also strongly associated with both poverty and social exclusion, and those who experience multiple dimensions of disadvantage are more likely to experience mental ill-health as an ongoing limiting factor in their lives rather than a short-term challenge that can be overcome.

Loneliness and isolation are increasingly recognised as significant public health concerns and these issues have been greatly exacerbated by the recent Coronavirus pandemic. The impacts have been felt across the population but have been particularly pronounced, with longer lasting impacts, for women and young adults (and young women in particular).Violence against women and girls services have also consistently reported victims experiencing significant mental ill health due to the impacts of COVID-19.

All graphs and tables can be found in the PDF here.

Key Findings

|

CONTENTS

Introduction

1. Overview of evidence on mental health and gender

2. Impact of COVID-19 on women and girls’ mental health

3. Impact of unpaid work on women and girls’ mental health

Introduction

This paper offers an overview of current evidence about mental health in Scotland, from a gendered perspective.

It provides a summary overview, and is intended to be accessible for people from all communities across Scotland regardless of whether or not they have existing knowledge about this area. As it is an overview it cannot examine every issue in depth. For more information about the topics discussed, please follow the references in the endnotes.

1. Overview of evidence on mental health and gender

Mental health is more than the absence of a mental disorder; it is a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to their community. Mental health is a state of balance which is constantly affected by physical, psychological, social, cultural, spiritual and other interrelated factors.

There is increasing evidence to suggest that mental health is a significant determinant of overall health. As a result greater emphasis is being placed on mental health and mental wellbeing as global public health priorities. Lifetime prevalence of mental health issues are higher than previously thought and affect nearly half the population in some fashion. Mental illness, however, is still widely underdiagnosed by doctors and underreported by patients.

Overall rates of psychiatric disorder are roughly the same for both men and women with little evidence to suggest gender differences in lifetime prevalence rates for high-impact, low-prevalence disorders (such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) but there are significant gendered differences with regards to patterns of mental ill health.

This is likely due to a number of factors, both socio-cultural and genetic. Gender determines differential power and control that men and women have, with specific differences in social position, status and treatment in society and exposure to specific mental health risks. Depression, anxiety and somatic symptoms (i.e. when a person experiences significant mental distress as a result of physical pain or fatigue) are significantly related to gender-based roles and negative life experiences more often experienced by women, such as gender based violence, socioeconomic disadvantage, low social status and continuous responsibility for the care of others.

The risk factors for women often intersect with a range of other social characteristics which are associated with higher levels of mental ill-health. Those who experience multiple dimensions of disadvantage are more likely to experience mental ill-health as an ongoing limiting factor in their lives rather than a short-term challenge that can be overcome.

There is also evidence that online culture and social media impact on the mental health of young women. Much of the research is correlational, meaning that it is not possible to prove that social media use directly leads to poor mental health, however the evidence available indicates that there is a strong association. Girls report high levels of intimidation and sexism online and many have experienced sharing of embarrassing, non-consensual or sexual photos, contributing to increased levels of shame, anxiety and depression. The Royal Society for Public Health and Youth Health Movement found that 90% of teenage girls say that they are unhappy with their bodies, while research by Girl Guides suggests that online pressure to conform to societally-based physical appearance norms impacts on women and girls’ self-esteem contributing to negative body image and increased mental distress.

There are also gender-based biases with regards to diagnosis and treatment of mental health disorders. Women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with depression even when showing identical symptoms or similar scores in standardised measures of depression. Women are more likely to seek help and disclose mental health problems to their primary health care physician. Men, on the other hand, tend to have lower health literacy and are less likely to report how they feel or seek help leading to delay in detection.

1.1 Mental Health in Scotland

Around one in four people are estimated to be affected by mental health problems in Scotland at any one time with women showing greater prevalence of rates of depression and anxiety, in line with global figures. Rates of suicide, however, remain consistently higher for men.

The Scottish Health Survey, a key source of data on the health and wellbeing of the population in Scotland, measures mental health and wellbeing in a number of ways. Mental distress and ill-health is measured using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) and mental wellbeing is measured using the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS). GHQ-12 is comprised of 6 positive and 6 negative items to assess positive and negative mental health. The GHQ-12 is scored on a range from 0 to 12, with a score of 4 or more indicative of probable mental ill health.

WEMWBS was developed as a tool for measuring mental well-being at a population level, the scale comprises 14 positively worded statements that relate to an individual’s state of mental well-being (thoughts and feelings). The overall score is calculated by totalling the scores for each item (the minimum possible score is 14 and the maximum is 70). The higher a person’s score, the better their level of mental well-being.

Details on depression and anxiety are collected via the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R). The CIS-R comprises of 14 sections, each covering a type of mental health symptom, and asks about presence of symptoms in the week preceding the interview. Participants of the Scottish Health Survey are also asked questions on suicide attempts and self-harm.

Mental wellbeing data for children in Scotland is collected using WEMWBS and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) which comprises of 25 items grouped into five scales covering emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems and pro-social behaviour. Total scores are calculated to give an overall SDQ score that falls into one of three categories ‘normal’, ‘borderline’ and ‘abnormal’.

GHQ-12

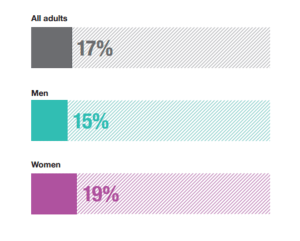

In 2019, the proportion of all adults with a GHQ-12 score of four or more

(indicative of a possible psychiatric disorder) was 17%. As in previous years, women were more likely than men to record a GHQ-12 score of four or more in 2019 (19% and 15% respectively), while the reverse was evident for the proportions recording a score of zero (56% of women compared with 62% of men). There was no significant difference in the proportions that recorded scores of between one and three by sex (25% among women and 23% among men).

Graph 1: Percentage of adults with GHQ-12 score of four or more, 2019

(Scottish Health Survey)

WEMWBS/SDQ

The mean WEMWBS score for adults in 2019 was 49.8, equal to that recorded in 2017 and not significantly different from 2018 (49.4). Similar patterns were evident for both men and women with no significant variations by sex in 2019.

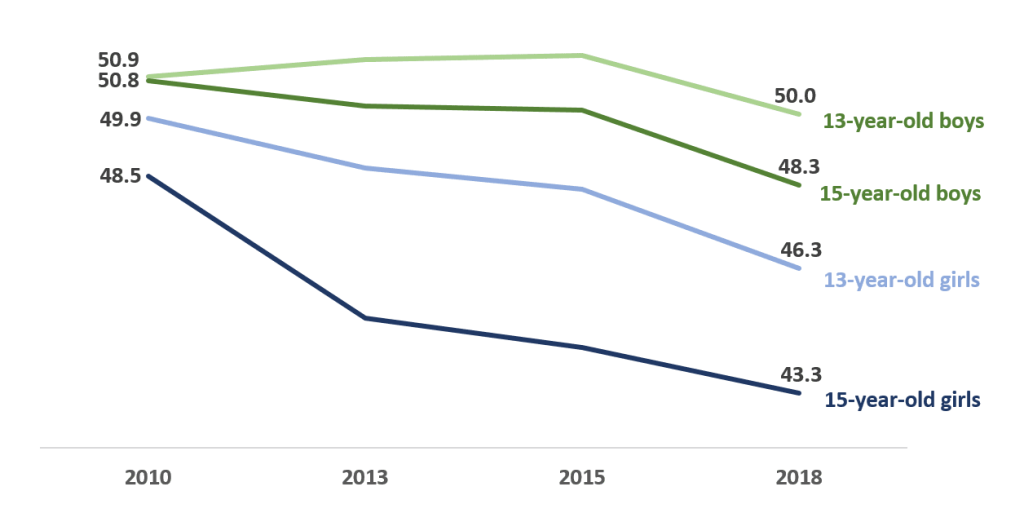

There is evidence to suggest, however, that adolescents’ mental wellbeing in Scotland has worsened in recent years, especially amongst adolescent girls, who report poorer mental wellbeing that boys of a similar age across a range of indicators.

The average WEMWBS score for schoolchildren in Scotland decreased from 48.4 in 2015 to 46.9 in 2018 with the greatest decreases seen among 13-year-old girls (from 48.2 to 46.3) and 15-year-old boys (from 50.1 to 48.3). 15-year-old girls continue to have the lowest wellbeing scores overall (43.3).

Graph 2: Mean WEMWBS score, by age and gender (2010-2018)

(Scottish Schools Adolescent Lifestyle and Substance Use Survey)

In 2018 63% of schoolchildren had a normal overall SDQ score while 18% had a borderline score and 20% had an abnormal score. The proportions of children with borderline or abnormal scores has been increasing since 2010 however the highest proportion continues to be amongst 15-year-old girls with over 4 in 10 (43%) reporting a borderline or abnormal total difficulties score. This is compared to 35% of 15-year-old boys.

CIS-R

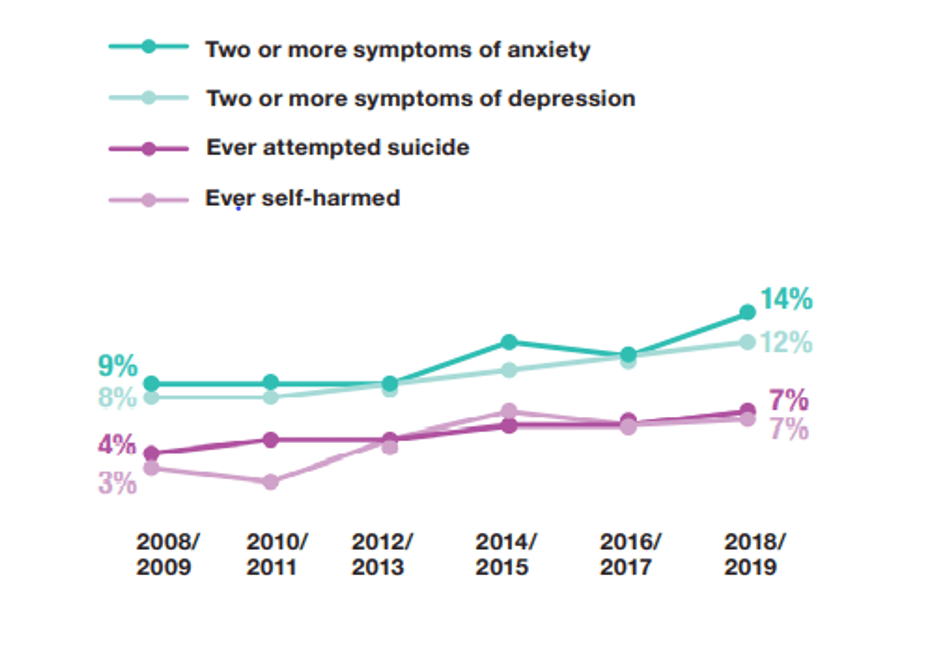

The trend of increasing prevalence of two or more symptoms of depression continued in 2018/2019 combined where the proportion was 12%. While not significantly higher than in 2016/2017 (11%), the 2018/2019 figure is the highest rate recorded in the time series, representing an overall increase from 9% in 2012/2013 (when the change in mode was introduced from nurse interview to self-complete) and 8% in 2010/2011.

The rate has fluctuated for women over time however it has remained at the highest level recorded across the time series in 2018/2019 (11%). The proportion of men, on the other hand, has increased steadily from 7% in 2010/11 to 12% in 2018/2019.

In 2018/2019, 14% of adults reported having two or more anxiety symptoms, the highest proportion in the time series compared with 9% in 2008/2009 and 2012/2013 (this can be seen in Graph 3, below). Over the time series (2008/2009 to 2016/2017), women have been more likely than men to display symptoms of anxiety (between 4 and 6 percentage points higher with the exception of 2010/2011 (2 percentage points higher)). However, the significant increase in men that reported two or more symptoms of anxiety in 2018/2019 and the absence of a significant increase for women means that the proportions of men and women reporting two or more symptoms of anxiety in 2018/2019 were not significantly different (13% and 15% respectively).

Graph 3: Rates of depression, anxiety, attempted suicide and self-harm, 2018/2019 combined

(Scottish Health Survey)

Women were also significantly more likely to have reported feeling lonely (often/all of the time) in the last two weeks compared with men (12% and 9% respectively). Prevalence was particularly high amongst younger women aged 16-24 (21%).

2. Impact of COVID-19 on women and girls’ mental health

2.1 Impact of COVID on mental health so far

Evidence from across the UK shows that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on many people’s mental health. This is especially true for young adults and women (and young women in particular), who had poorer mental health beforehand. Mental health inequalities have therefore widened overall.

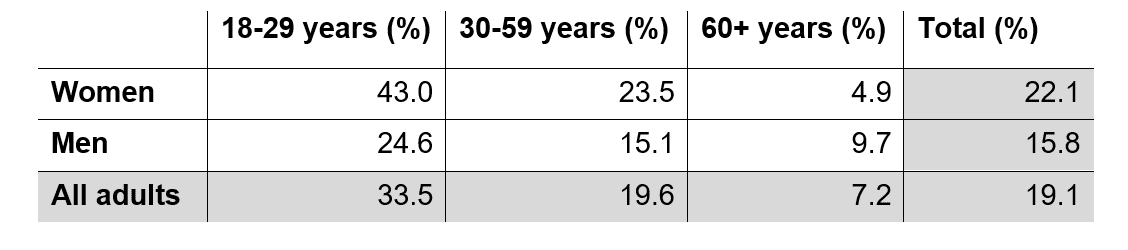

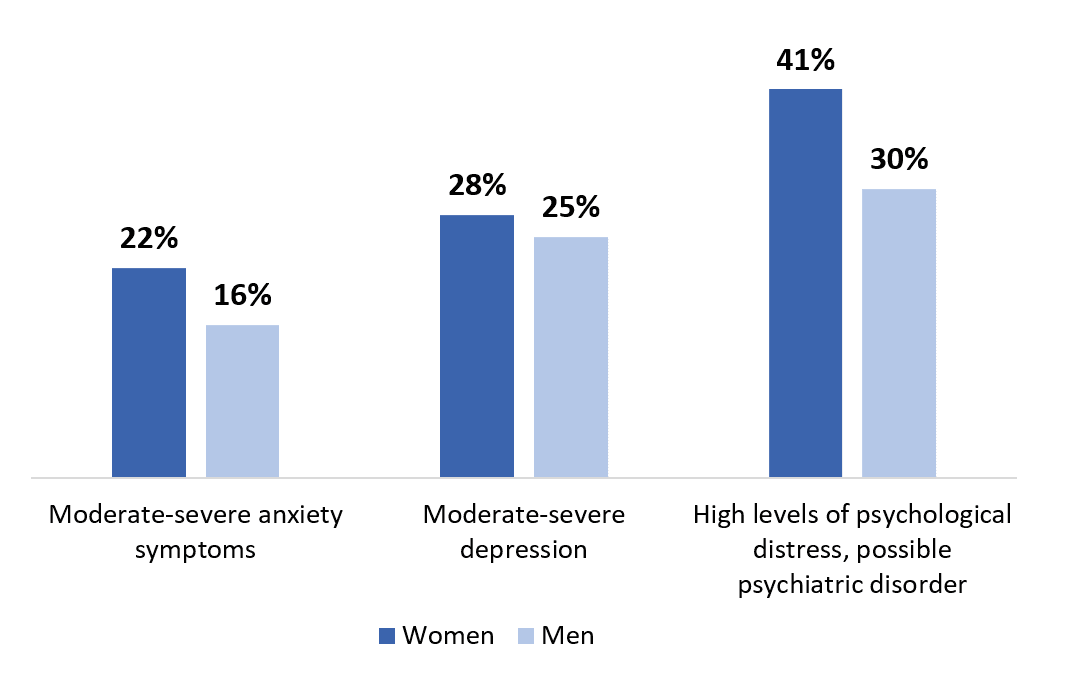

The Scottish COVID-19 Mental Health Tracker Study (SCOVID) found that in May-June 2020, women reported higher rates of moderate to severe anxiety symptoms than men, indicating possible generalised anxiety disorder and a possible need for treatment (22.1% compared to 15.8%). Young women aged between 18-29 years reported markedly higher rates of moderate to severe anxiety symptoms (43.0%) than younger men (24.6%). Older women, however, reported the lowest levels of anxiety symptoms (4.9%) of the sample, which was nearly half that of the older men’s rate of 9.7%, as Table 2 shows.

Table 1: Moderate to severe anxiety symptoms by age and gender, May-June 2020

(Scottish COVID-19 Mental Health Tracker Study)

Women were also somewhat more likely than men to meet the cut-off for depressive symptoms, indicating moderate to severe depression (27.6% and 25.3% respectively). Furthermore, young women between 18-29 years old reported higher rates of depressive symptoms at 50.9%, compared to 38.9% of men in the same age group. Overall, 10.2% of respondents reported suicidal thoughts within the week prior to the Wave 1 questionnaire. There were no differences between men and women in levels of suicidal thoughts reported, however young women reported the highest rates of suicidal thoughts in the past week (24.3%) – higher than that of young men (18.1%). Women also reported more self-harm in the last week (2.1%) compared to men (0.5%), and this was highest for women aged 18-29 years old (5.3%).

A greater proportion of women than men scored above the GHQ-12 cut-off score indicating high levels of psychological distress and a possible psychiatric disorder (40.8% vs 30.3%). In comparison, 19% of women and 15% of men recorded these scores in the 2019 Scottish Health Survey. Young women were also more likely in the SCOVID Mental Health Tracker study to have a high GHQ-12 score (58.5%) compared to young men (45%).

Graph 4: Proportions of people reporting various symptoms of poor mental health, by gender, May-June 2020

(Scottish COVID-19 Mental Health Tracker Study)

The SCOVID Mental Health Tracker Study also assessed a range of other indicators and correlates of mental health and wellbeing. These included feelings of defeat, entrapment, loneliness, resilience, social support, life satisfaction, and distress. Findings suggest that, again, the subgroups most at risk of poor mental health and wellbeing include women and young adults (18-29 years). Those with a pre-existing mental health condition and those in lower socio-economic groups were also more at risk.

Loneliness was measured using 3 items, with a score of 3 indicating no loneliness and a score of 9 equating to very high loneliness. Women reported higher levels of loneliness than men (5.32 vs. 5.02). In terms of support networks however, women were slightly more likely to feel connected to family (70.1%) than men (65.1%), and more women also reported feeling more connected to friends (47.8%) than men (40.3%). Men, on the other hand, were more likely to feel connected to colleagues (26.7%) than women (20.4%).

Defeat and entrapment were assessed using short forms of established scales, with l respondents given a score for each measure between 0 (indicating no feelings of defeat or entrapment) and 16 (indicating a very high level of feelings of defeat and entrapment). Women also reported higher mean scores on defeat (4.42) than men (3.55), and women reported higher levels of feeling entrapped (4.01) than men (3.38). Feelings of defeat and entrapment are important indicators of mental health, and have been associated with depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts. Defeat is a feeling of powerlessness in life and entrapment is a feeling of being trapped by circumstances or your own thoughts.

The survey also asked people about experiences and outlets for stress. Women were slightly more likely to report feeling cut off from friends and family (48.7%) compared to men (42.7%). Women also felt that they were struggling with the restrictions on socialising (25.7%) more than men (20.3%); they were more likely to report poor sleep (40.9%) compared to men (29.2%); and to report having less of a sense of purpose (35.7%) compared to men (24.5%). Further, women were more likely to report feeling there was not enough space in the home (14.1%) compared to men (10.1%) and an increase in arguments with those they lived with (16.4%, vs 8.8% for men).

When asked specifically about COVID-19, women reported feeling that their life had been more severely affected by COVID-19 than men did, as well as reporting higher levels of emotional affect than men did. Minority ethnic respondents and those with a pre-existing mental health condition also reported significantly higher emotional impact of COVID-19 than those who identified as White and those with no pre-existing mental health condition. Overall, women were more concerned about COVID-19 than men.

Evidence from Great Britain and the UK more widely largely reflect these findings in Scotland. ONS found that women in Great Britain were more likely to say that the COVID-19 outbreak was affecting their well-being (for example, boredom, loneliness, anxiety and stress) than men, at the end of June (53% vs 37%).More recent ONS data showed that this gender difference remained at the start of November (56% of women and 42% of men). Understanding Society has found higher levels of psychological distress among women than men, while Ipsos MORI surveys conducted during the lockdown found that women were more likely than men in Britain to have been finding it harder to stay positive day-to-day, compared with before the outbreak. Other analysis of this data finds that the impact of COVID-19 on mental health is concentrated in younger age groups among men, whereas women of all ages were negatively affected.

There is evidence that stress and anxiety has been higher in girls than boys during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that there has been a small but noticeable decline in girls’ wellbeing. GirlGuiding surveyed girls and young women aged 4-18 across the UK about their experiences of COVID-19 and lockdown in May 2020. They found that a quarter of the girls aged 11-14 who responded (24%) and half of those aged 15–18 who responded (51%) reported coronavirus and lockdown having a negative impact on their mental health. High proportions of respondents said that social isolation was putting a strain on their relationships at home, and older girls were very worried about the future and falling behind at school or college.

It is reported that pre-COVID, 84% of single parents reported being lonely and there is growing evidence to suggest that lockdown exacerbated loneliness amongst lone parents. The vast majority of single parents are women (87% in 2011). In England, plans for support bubbles were criticised for overlooking the fact the majority of single parents rely on formal childcare and do not necessarily have a support network to create a bubble with. It has also been suggested that digital exclusion combined with social distancing poses a risk of further inequality and loneliness for particular groups of women – poor women, mothers, carers, minority ethnic women and older women. Women without internet access and who are experiencing domestic abuse are a huge concern.

People with experience of mental health issues have been particularly concerned about social isolation during the pandemic, while Glasgow Disability Alliance have highlighted that over 70% of the disabled people that they surveyed during the pandemic were worried about becoming acutely isolated. This related partly to lack of internet access, and also that many rely on others for support with day to day tasks and looking after themselves.People with learning difficulties and neurodevelopmental disorders may be particularly affected by changes and disruption to support and routines, isolation, and loneliness. Older people may also be at greater risk of social isolation due to being less likely to use online communication.

Despite the NHS remaining open for those who need urgent care, figures are also indicating that patients have been delaying accessing healthcare during the pandemic, especially at the start. Particularly large decreases in the number of children using services has been seen. There are also likely to be negative health impacts from delays to preventative and non-urgent care. Around a quarter (26%) of adults in Great Britain said that their access to healthcare and treatment for non-coronavirus related issues is being affected by COVID-19 as of early November, with women more likely than men to say this (30% vs 22%, 5-8 November). Research conducted by the Fawcett Society similarly found that women in the UK expressed slightly more concern than men overall about access to NHS treatment and medicine during the pandemic. While these findings do not specifically relate to mental health care, they are likely to be indicative.

2.2 COVID-19, violence against women and girls, and mental health

Many violence against women and girls services reported during lockdown (March-May 2020) that service users with pre-existing mental health conditions were negatively affected, with anxiety and depression being exacerbated by isolation and living with domestic abuse. There were also reports of high levels of anxiety among clients over whether or not those convicted of domestic abuse would be released.

During the period from May-August 2020, violence against women and girls services consistently reported victims experiencing significant mental ill health due to the impact of COVID-19. Organisations reported victims cited the combined impact of isolation, lack of safe childcare options, managing the risk of domestic abuse and the risk of the virus to have a severe impact on their mental health and resilience. Some victims of domestic abuse reported their lack of options for ’emotional safety-planning’ (attending safe spaces such as churches and/or sporting, parenting or community groups) impacted negatively on their mental health. The impact was also particularly acute for women involved in prostitution/commercial sexual exploitation, due to the unknown end date and financial and economic impacts of the Coronavirus restrictions.

Many organisations observed increases in crisis work with victims, with many people experiencing suicidal ideation, depression and anxiety, increasing substance misuse as a coping mechanism, and/or increased levels of fear, both of the perpetrator and the virus. Organisations observed that victims required increased support, with many contacting services several times a week and requiring extended support calls. A number of services report that low mood and trauma triggers appear to be a recurring feature for the most isolated women.

Domestic abuse often has a number of negative impacts on the mental health of those experiencing it, which can include low self-esteem, anxiety or panic attacks, depression, fear, difficulty sleeping/nightmares, self-harm and suicide attempts. Low self-esteem was the most commonly reported of these in 2017-18 (especially by women). It can also significantly negatively impact the mental health of children who are exposed to it. Women, younger people (16-24) and those living in more deprived areas are all more likely to report experiencing domestic abuse, as are those of mixed ethnicity, disabled people and those living in a single-parent household according to data from England and Wales.

2.3 Future impacts of COVID on women and girls’ mental health

The longer term health implications of contracting COVID-19 remain largely unknown, but there are growing concerns around this. A recent study from the US suggests that people who have contracted COVID-19 may be at increased risk of developing mental health conditions, although the research did not analyse their results by gender.

Social isolation is associated with anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicide attempts across the lifespan; an increase in social isolation during the pandemic and lockdown could therefore have serious mental health consequences for those affected. The gendered aspect of this is not yet clear: there are more women than men in older age groups and among disabled people, groups who have been advised to isolate during the pandemic, however we know that women were more likely than men to meet socially with friends, family, relatives, neighbours or work colleagues at least once a week before the pandemic (2018). People living with a long-term physical or mental health condition were less likely to meet socially, however.

There have also been reports internationally of negative mental health impacts for healthcare workers on the frontline of the pandemic. These may have lasting effects if treatment and support is not provided. Healthcare workers are disproportionately likely to be women and those of visible minority ethnicities are also more likely to be working in healthcare – 77% of those working in Human health activities in Scotland in 2018-19 were women, and 7% were of a visible (non-White) minority ethnicity.

Furthermore, mental health also impacts upon physical health, so worsening mental health during the pandemic indicates future indirect impacts on health (and subsequently other interrelated areas).

3. Impact of unpaid work on women and girls’ mental health

Women in the UK are far more likely to provide unpaid labour (often in the form of childcare, housework, shopping or other caregiving). ONS analysis from 2016 found that, on average, men do 16 hours a week of this kind of unpaid work, compared to 26 hours done by women. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic the impacts of this disproportionate unpaid workload has led to a significant increase of mental distress.

The last 10 years has seen an increase in the intensity of work with nearly half of the British workforce reporting ‘always’ or ‘often’ feeling exhausted when they return home from work (55% of women and 47% of men). The UK is also well above the EU average for amount of hours worked per week (42.0 compared to 40.2).

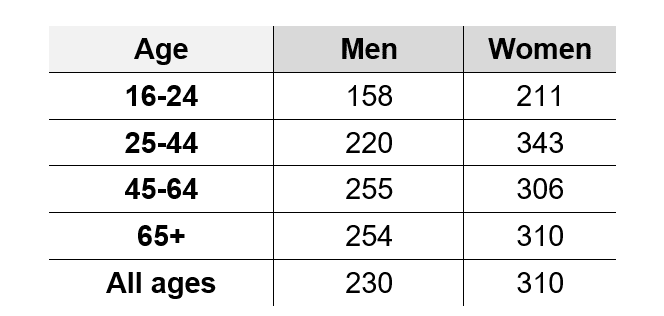

Scottish data suggests that women spend significantly more time overall on unpaid work than men (310 and 230 minutes respectively). The differences are particularly apparent for women in the 25-44 and 65+ age groups. When broken down into the nine components that make up the term ‘unpaid work’ (housework; shopping; services and household management; construction and repairs; caring for one’s own children; caring for other people’s children; gardening and pet care; travel; help to others; and volunteering) women spent significantly more time than men on housework, shopping, services and household management and caring for one’s own children. Men spent significantly more time on construction and repairs and travel. The other components saw no significant gendered differences.

Table 2: Mean minutes spent on unpaid work by age and gender in Scotland, 2014/15

(Centre for Time Use, Oxford University)

Changes in schooling and provision of childcare as a result of lockdown and restrictions has meant that women are spending an increasing amount of time at home on unpaid work on top of their usual paid workload. When increased paid workload intensity is coupled with an increase in the already disproportionate unpaid workload faced by women (due to the closure of schools, etc) it is unsurprising that mental distress has grown significantly.

References

For the full list of references, graphs, tables and a downloadable PDF please follow this link.

Data sources drawn on in this report collect self-reported data on whether respondents are male or female. The term gender is therefore used throughout this report, although though some data sources use the term sex in their research.

[1] New data on this will be published on the 16th of December, 2020

[1] National Institute of Mental Health, Women and Mental Health. Available at: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/women-and-mental-health/index.shtml

[2] World Health Organization (2017). Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2- eng.pdf?sequence=1

[3] Murali, Vijaya, and Femi Oyebode. “Poverty, social inequality and mental health.” Advances in psychiatric treatment 10.3 (2004): 216-224.

[4] Payne, Sarah. “Mental health, poverty and social exclusion.” Poverty and social exclusion in Britain: The millennium survey (2006): 285-311.

[5] Scottish Government, 2020, Coronavirus (COVID-19): mental health – transition and recovery plan. Available at: Coronavirus (COVID-19): mental health – transition and recovery plan – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[6] Scottish Government, 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19): mental health tracker study – wave 1 report. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-covid-19-scovid-mental-health-tracker-study-wave-1-report/pages/2/ [accessed 19 November 2020] ; ONS (2020). Coronavirus and the economic impacts on the UK: 10 September 2020. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/business/businessservices/bulletins/

coronavirusandtheeconomicimpactsontheuk/10september2020

[7] WHO, 2018, Mental health: strengthening our response, Available at: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

[8] WHO, 2020, Gender and women’s mental health. Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/gender-and-women-s-mental-health

[9] Wilhelm, Kay A. “Gender and mental health.” Australian & New Zealand journal of psychiatry 48.7 (2014): 603-605.

[10] Uddin, Monica, et al. “Gender differences in the genetic and environmental determinants of adolescent depression.” Depression and anxiety 27.7 (2010): 658-666.

[11] Mental Health Foundation, 2017, While Your Back Was Turned: How mental health policymakers stopped paying attention to the specific needs of women and girls. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/while-your-back-was-turned-how-mental-health-policymakers-stopped-paying-attention-to-mental-health-needs-young-women-girls.pdf

[12] Barthorpe, Amber, et al. “Is social media screen time really associated with poor adolescent mental health? A Time Use Diary Study.” Journal of Affective Disorders (2020).

[13] Girlguiding UK (2016) Girls’ Attitudes Survey: 2016. Available at: https://www.girlguiding.org.uk/globalassets/docs-and-resources/researchand-campaigns/girls-attitudes-survey-2016.pdf

[14] Royal Society for Public Health and Young Health Movement (2017) #Status of Mind: Social media and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. Available at: https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-work/policy/social-media-and-young-peoples-mental-health-and-wellbeing.html

[15] Girlguiding UK (2016) Girls’ Attitudes Survey: 2020. Available at: https://www.girlguiding.org.uk/girls-making-change/girls-attitudes-survey/

[16] WHO, 2020, Gender and women’s mental health. Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/gender-and-women-s-mental-health

[17] WHO, 2020, Gender and women’s mental health. Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/gender-and-women-s-mental-health

[18] Cochran, SR, Rabinowitz, FE (2000) Men and Depression: Clinical and Empirical Perspectives. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

[19] Scottish Association for Mental Health, Understanding Mental Health. Available at: https://www.samh.org.uk/documents/understandingmentalhealthproblems.pdf

[20] World Health Organization (2020). Depression Fact Sheet. Available from: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

[21] World Health Organization (2017). Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2- eng.pdf?sequence=1

[22] Scottish Government, 2020. Scottish Schools Adolescent Lifestyle and Substance Use Survey (SALSUS). https://www.gov.scot/collections/scottish-schools-adolescent-lifestyle-and-substance-use-survey-salsus/#salsustimetrendsdataset [accessed 2 December 2020].

[23] IFS, 2020. The mental health effects of the first two months of lockdown and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Available at: https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14874 [accessed 19 November 2020] ; ONS, 2020. Coronavirus and depression in adults, Great Britain: June 2020. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/

coronavirusanddepressioninadultsgreatbritain/june2020 [accessed 19 November 2020] ; ONS, 2020. Coronavirus and anxiety, Great Britain: 3 April 20202 to 10 May 2020. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/

coronavirusandanxietygreatbritain/3april2020to10may2020 [accessed 19 November 2020].

[24] Scottish Government, 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19): mental health tracker study – wave 1 report. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-covid-19-scovid-mental-health-tracker-study-wave-1-report/pages/2/ [accessed 19 November 2020].

[25] Scottish Government, 2020. Scottish Health Survey 2019 – Volume 1: main report. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-health-survey-2019-volume-1-main-report/pages/5/ [accessed 19 November 2020].

[26] ONS, 2020. Coronavirus and the social impacts on Great Britain: 3 July 2020. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/

bulletins/coronavirusandthesocialimpactsongreatbritain/3july2020 [accessed 19 November 2020].

[27] ONS, 2020. Coronavirus and the social impacts on Great Britain: 13 November 2020. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/

coronavirusandthesocialimpactsongreatbritain/13november2020 [accessed 19 November 2020].

[28] Understanding Society, 2020. COVID-19 Survey. Briefing Note: Wave 1, April 2020. Health and Caring. Available at: https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/sites/default/files/downloads/general/ukhls_briefingnote_covid_health_final.pdf [accessed 19 November 2020] ; Ipsos MORI, 2020. Gender differences in attitudes towards Coronavirus. Available at: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-05/fawcett_society_presentation.pdf?platform=hootsuite [accessed 19 November 2020].

[29] IFS, 2020. The mental health effects of the first two months of lockdown and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Available at: https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14874 [accessed 19 November 2020].

[30] Scottish Government, 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19): impact on children, young people and families – evidence summary June 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/report-covid-19-children-young-people-families-june-2020-evidence-summary/ [accessed 2 December 2020] ; Scottish Government, 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19): impact on children, young people and families – evidence summary September 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/report-covid-19-children-young-people-families-september-2020-evidence-summary/ [accessed 2 December 2020].

[31] GirlGuiding, 2020. Girlguiding research briefing: Early findings on the impact of Covid-19 on girls and young women. Available at: https://www.girlguiding.org.uk/globalassets/docs-and-resources/research-and-campaigns/girlguiding-covid19-research-briefing.pdf [accessed 2 December 2020].

[32] One Parent Families Scotland, 2020. Response to COVID-19. Available at: https://opfs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Response_to_COVID-19_OPFS.pdf [accessed 19 November 2020] ; See for example, Ibid & Save the Children, 2020. Lockdown Life as a Single Parent. Available at: https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/blogs/2020/lockdown-life-as-a-single-parent [accessed 19 November 2020].

[33] NRS, 2015. Household composition for specific groups of people in Scotland. Scotland’s Census 2011. Available at: https://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/documents/analytical_reports/HH%20report.pdf [accessed 19 November 2020].

[34] Independent, 2020. ‘I’m unable to breathe I’m so stressed’: Single parents warn support bubbles fail to address financial dilemmas. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/coronavirus-support-bubbles-single-parents-a9561571.html [accessed 19 November 2020].

[35] Engender, 2020. Engender submission of evidence to the UK Parliament Women and Equalities Committee inquiry on Unequal impact: Coronavirus (Covid-19) and the impact on people with protected characteristics. Available at: https://www.engender.org.uk/content/publications/Engender-submission-of-evidence-Women-and-Equalities-Committee-Covid19.pdf [accessed 19 November 2020].

[36] E. Holmes et al., 2020. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19

pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanpsy/PIIS2215-0366(20)30168-1.pdf [accessed 19 November 2020] ; Glasgow Disability Alliance, 2020. Pandemic Frontline. Available at: https://mailchi.mp/gdaonline/covid-19-supercharges-existing-inequalities-faced-by-glasgows-150000-disabled-people?e=35607ddbb9 [accessed 19 November 2020].

[37] E. Holmes et al., 2020. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19

pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanpsy/PIIS2215-0366(20)30168-1.pdf [accessed 19 November 2020].

[38] M. Douglas et al., 2020. Mitigating the wider health effects of covid-19 pandemic response. Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/369/bmj.m1557.full.pdf [accessed 19 November 2020].

[39] Scottish Government, 2020. Urgent Medical Help Still Available ; Public Health Scotland, 2020. COVID-19 Wider Impacts on the Health Care System. Available at: https://scotland.shinyapps.io/phs-covid-wider-impact/ [accessed 19 November 2020].

[40] ONS, 2020. Coronavirus and the social impacts on Great Britain: 13 November 2020. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/

coronavirusandthesocialimpactsongreatbritain/13november2020 [accessed 19 November 2020].

[41] Fawcett Society, 2020. Coronavirus: Impact on BAME women. Available at: https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/coronavirus-impact-on-bame-women [accessed 19 November 2020].

[42] Scottish Government, 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19): domestic abuse and other forms of violence against women and girls – 30/3/20-22/05/20. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/domestic-abuse-forms-violence-against-women-girls-vawg-during-covid-19-lockdown-period-30-3-20-22-05-20/pages/3/ [accessed 19 November 2020].

[43] Scottish Government, 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19): domestic abuse and other forms of violence against women and girls during Phases 1, 2 and 3 of Scotland’s route map (22 May to 11 August 2020). Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-domestic-abuse-forms-violence-against-women-girls-during-phases-1-2-3-scotlands-route-map-22-11-august-2020/pages/5/

[44] Scottish Government, 2019. Scottish Crime and Justice Survey 2017/18: Main Findings. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-crime-justice-survey-2017-18-main-findings/pages/13/#_9.3_Partner_Abuse [accessed 19 November 2020].

[45] J. Fegert, B. Vitiello, P. Plener & V. Clemens, 2020. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Available at: https://capmh.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3 [accessed 19 November 2020].

[46] Scottish Government, 2019. Scottish Crime and Justice Survey 2017/18: Main Findings. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-crime-justice-survey-2017-18-main-findings/pages/13/#_9.3_Partner_Abuse [accessed 19 November 2020] ; ONS, 2019. Domestic abuse victim characteristics, England and Wales: year ending March 2019. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/

domesticabusevictimcharacteristicsenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2019#ethnicity [accessed 19 November 2020].

[47] E. Holmes et al., 2020. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19

pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanpsy/PIIS2215-0366(20)30168-1.pdf [accessed 24 November 2020] ; A. Dasgupta, A. Kalhan & S. Kalra, 2020. & S. Kalra, 2020. Long term complications and rehabilitation of COVID-19 patients. Available at: https://europepmc.org/article/med/32515393 [accessed 24 November 2020] ; C. Morris, 2020. Coronavirus: Why surviving the virus may be just the beginning. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/53193835 [accessed 24 November 2020].

[48] M. Taquet et al, 2020. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(20)30462-4/fulltext [accessed 24 November 2020].

[49] E. Holmes et al., 2020. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19

pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanpsy/PIIS2215-0366(20)30168-1.pdf [accessed 19 November 2020] ; M. Douglas et al., 2020. Mitigating the wider health effects of covid-19 pandemic response. Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/369/bmj.m1557.full.pdf [accessed 19 November 2020].

[50] NRS, 2020. Mid-2019 Population Estimates, Scotland. Available at: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/population/population-estimates/mid-year-population-estimates/mid-2019 [accessed 24 November 2020] ; Scottish Government, 2020. Scottish Health Survey 2019 – volume 1: main report. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-health-survey-2019-volume-1-main-report/ [accessed 24 November 2020]. Scottish Government, 2019. Scottish household survey 2018: annual report. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-people-annual-report-results-2018-scottish-household-survey/pages/4/ [accessed 24 November 2020].

[51] R. Rossi et al., 2020. Mental health outcomes among front and second line health workers associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Available at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.16.20067801v1 [accessed 19 November 2020] ; J. Lai et al., 2020. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. Available at: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2763229 [accessed 19 November 2020] ; N. Greenberg, 2020. Mental health of health-care workers in the COVID-19 era. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41581-020-0314-5 [accessed 19 November 2020].

[52] N. Greenberg et al., 2020. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/368/bmj.m1211 [accessed 19 November 2020].

[53] Annual Population Survey, ONS, April 2018 – March 2019.

[54] IFS, 2020. The mental health effects of the first two months of lockdown and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Available at: https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14874 [accessed 19 November 2020].

[55] ONS, 2016, Women shoulder the responsibility of ‘unpaid work’, Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/

womenshouldertheresponsibilityofunpaidwork/2016-11-10

[56] N. Murray, 2020. Burnout Britain: Overwork in an Age of Unemployment. Available at: https://www.compassonline.org.uk/publications/burnout-britain-overwork-in-an-age-of-unemployment/

[57] Felstead, A., Green, F., Gallie, D. & Henseke, G. (2018) Work Intensity in

Britain: First Findings from the Skills and Employment Survey 2017. Cardiff: Cardiff

University. Available at: https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/research/explore/find-aproject/

view/626669-skills-and-employment-survey-2017

[58] Eurostat (2020). Average number of usual weekly hours of work in main job, by sex, professional status, full-time/part-time and occupation (hours). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/LFSA_EWHUIS

[59] Scottish Government, 2019, Time use survey 2014-2015: results for Scotland. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/centre-time-use-research-time-use-survey-2014-15-results-scotland/